Borders, threads, and the unraveling of narrative

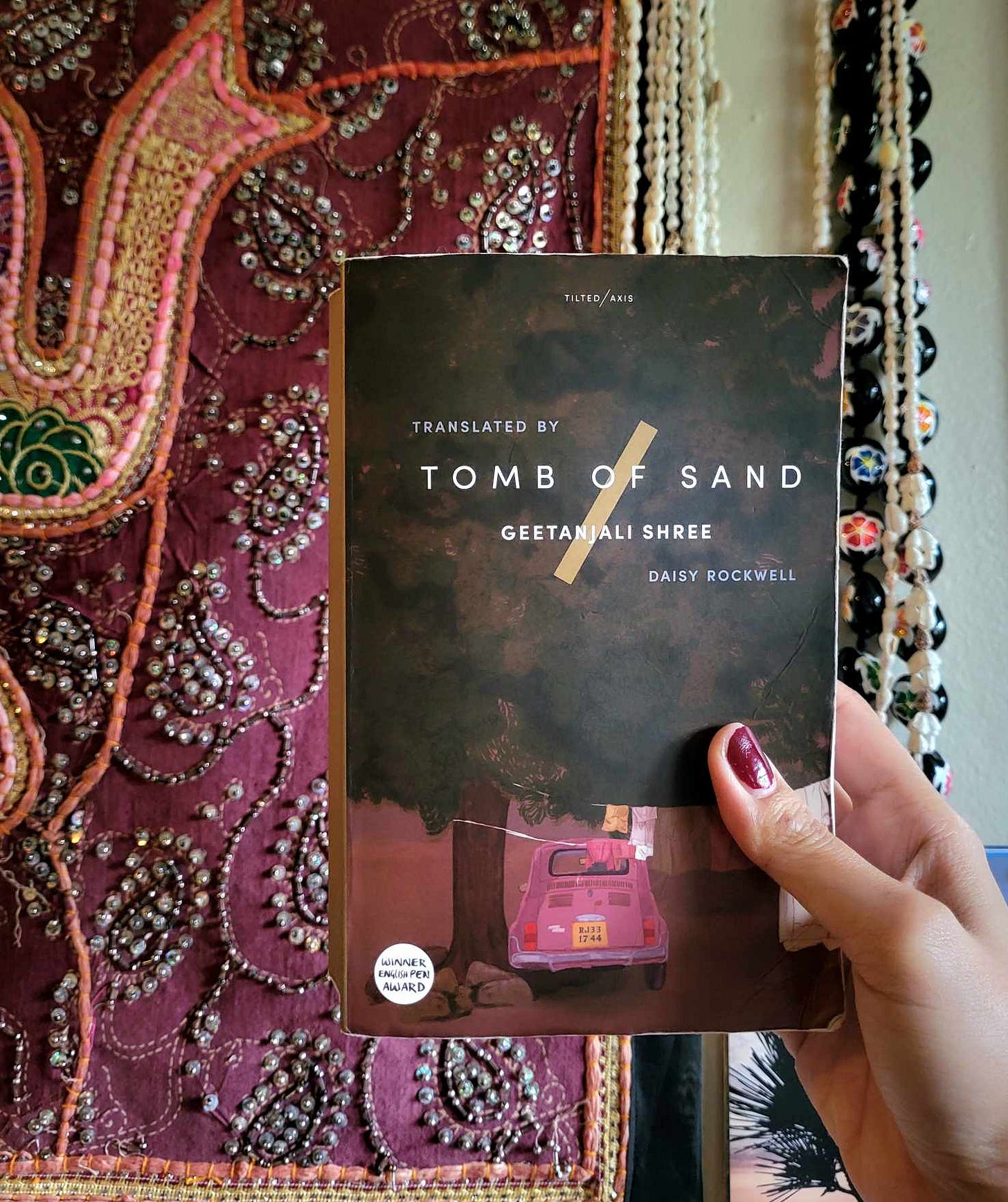

A book review of Tomb of Sand by Geetanjali Shree, translated by Daisy Rockwell

In the world of reviewing and discussing books, you’ll typically run into phrases like “weaving threads” and “at once, x and y” to illustrate the layeredness of storytelling. It’s interesting how in a world where efficiency and optimizing are increasingly valued, we still turn to the topsy turvy and chaotic to escape. Maybe even moreso as we get pummeled with short-form content on how to hack our exercise, reading, eating, sleeping, speaking, etc. In my reading appetite, a good, hearty novel that stays on the mind holds space for narratives that are rarely straightforward, never efficient. Fiction is where we luxuriate in metaphor, let the author string us along the story with no promises of ever getting to a conclusion. Story is not about conclusion, but the threads that make up an ending.

Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand is one of the most inefficient and exhausting novels I’ve ever come across. At the same time, I’m starting to believe that it’s one of the best examples of storytelling we have. A story of Partition, aging, familial dynamics, feminism, migration, borders, crows, textiles – it’s a masterpiece of woven narrative.

The novel starts with a disclaimer and warning:

“A tale tells itself. It can be complete, but also incomplete, the way all tales are. This particular tale has a border and women who come and go as they please. Once you’ve got women and a border, a story can write itself.”

As she promises, Shree’s narrative meanders and tricks the reader into infinite rabbit holes of language and plot. Here is a story of the widowed Ma finding joy and life again after her husband dies. There is a story of her grown children and their reactionary tales to the family dynamics that have either served as molds or repellants in how they shape their lives. Over yonder is a story of a land ripped down the middle, of lives thrown across drawn lines, haphazard and merciless. Look closer and it’s actually a story of womanhood and the woman’s body. What shapes dictate who we are, and what are the borders drawn on history, identity, life?

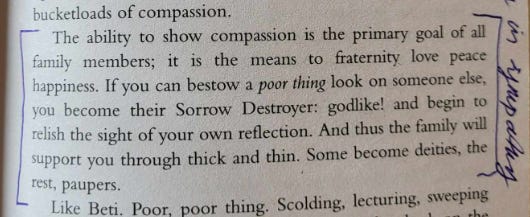

I read this book over several months, some of them spent in India, where our story takes place, observing and living through some of the family and gender dynamics that loom over the story. Ma, her daughter Beti, daughter-in-law Bahu, and the hijra Rosie serve as four archetypes of women: all separated in social strata, age, physicality, and beliefs. It was especially interesting to note the deferential treatment to age and femininity, and how they blurred into a deification, then consequential dehumanization, of Ma herself. What was once the pinnacle of womanhood, draped elegantly in a sari, unraveled into obscurity and obscenity as soon as Ma stepped away from expected, respected behavior. Socializing with someone like Rosie, wearing shapeless garments, and giving away her worldy treasures, Ma challenges both traditional Bahu and unorthodox Beti into rethinking their own womanhood and “place” in society, how their subversion and obeiance begin to intertwine when boxed into the same patriarchal structure.

As a new bahu myself, I’ve found it difficult but exhilarating to explore another culture’s family and gender dynamics, with baggage from my own family’s Filipino Catholic background in tow. Translations of language, belief, and expectations are currencies in my old and new families; it was simultaneously comforting and distressing to read in Shree’s novel that these currencies are perpetually necessary and never consistent.

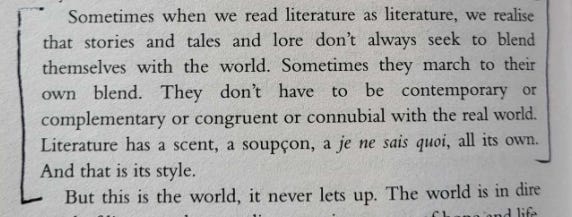

Translated from Hindi into English, the transformed novel takes care of itself in stubborn preservation. In her translation note, Daisy Rockwell speaks on the melody of Hindi, and how a translated work can never fully capture the true spirit of original voice. There are words that simply do not exist in English, whether because we lack the contextual understanding or the syntactic rhythm. This brought back to mind the idea of movement and migration, both forced and voluntary, and how stories translated through time, language, and geography often go through their transformations through the decades and centuries. Ma’s story was born in Lahore in a time with no borders; it ends along a border she defiantly ignores and hops along like a game.

At the end of this journey I was left dazed and awed, not unlike walking through mist for hours to find that the end is almost visible, though still altered in my eyes. Shree’s story has unraveled, pinned, and rewoven itself with me, leaving both of us transformed. This novel will remain on my mind for a while, its translations and transformations a mark of true storytelling, unapologetic and bashful, deceptive and true.